As we approached the front door of the Georgian country home where Georgette’s Heyer’s archive is kept—with its manicured gardens, classic sash windows, and sweeping drive—I felt that but for the SUV we were driving we might be characters in one of Heyer’s own novels.

We were visiting the home of Lady Rougier to photograph and document Heyer’s archive of research. We already knew that her Regency novels were as famed for their historical accuracy as their gripping plots—that Heyer was as much a historian as she was a novelist. Even so, the thought made me nervous. This wasn’t exactly the British Library. I pictured neglected cardboard boxes full of loose notes, inscrutable handwriting, and faded photographs.

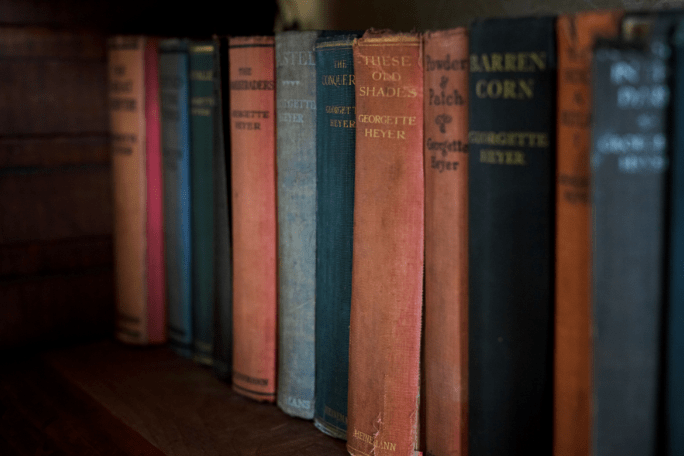

Lady Rougier led us through the converted barn that was now a TV and games room, to a small cabinet in the corner. Inside, neatly lined up, were a dozen notebooks and photo albums and a few cases of note cards. Was this it? A life’s work barely filled two shelves. Breathlessly, delicately, we opened the first notebooks as our photographer set up his equipment. I wasn’t prepared for how intimate it would feel to see Heyer’s neat handwriting on the page.

Georgette’s perfect script exemplified her deep, careful research. Hundreds of pages of words and phrases organised by category: pugilism, manners and papacy, fashion, and beauty. Reference images cut and pasted from Regency magazines and antiques catalogues. Family trees of the Royals, and the real-life whereabouts of kings and queens during major social events throughout the years. Heyer was no mere hobbyist. She consumed every conceivable facet of Regency England, and wore her hard-won expertise like clothes, so that she could deliver a timeless set of historical novels that felt authentic—as though they were written in the time they depict.

Our kind host brought us cups of tea and plates of sausage rolls as we underwent the task of documenting Heyer’s research. The process took hours, but as each page revealed more details of her methodical process, we found ourselves becoming as enamoured with Heyer the historian as we already were with Heyer the novelist.

Alongside the research notes was marginalia. Little notes-to-self, sketches and doodles that brought Heyer ever more to life in our minds. Yes, here was the incisive mind of the woman described by Queen Elizabeth II as “formidable,” but here too was the proud writer who cherished her fan letters; the wry sense of humour which delighted in the scathing Regency-era insults that seem nonsensical today; the ingenue novelist who kept note of her first publishing advances on the cover pages of her typed-up proofs.

In photographing Heyer’s research we had hoped to preserve her work and legacy—to freeze it in time. But instead, the process brought her to life. She became as real to us as her timeless, beloved characters. And, for a short time among pots of tea and the smell of old, yellowing paper, ‘Heyer’ had become ‘Georgette’.

Jeremy Barclay, June 2023